Heritage Through Folk

Oevaali Art Shop Exhibition 2018

Maldivian folklore is as rich in mysticism and wonder as the islands themselves, and lays out bare the lives of our indigenous ancestors. The oral tradition of the Dhivehi people have preserved an important past, and offers more than simply history; it bonds together the dead, the living, and those yet to be born.

Heritage through Folk by Oevaali Art Shop weaves together a rich, captivating narrative of art from over 10 prolific Maldivian artists. Featuring individual iconic styles, these recollections and interpretations of old Maldivian tales delve deeper into our heritage, and taken as a whole, reflects the complexities of telling the Maldivian story.

The exhibition explores issues of our authentic identity and self; what it means to have indigenous ancestors, and a history intertwined with folk tales, tradition and mysticism.

With heartfelt thanks to

Raniya Mansoor

Curator, Heritage Through Folk 2018

Exhibiting Artists

Curator, Heritage Through Folk 2018

Exhibiting Artists

- Raya Mansoor

- Raniya Mansoor

- Imma Rasheed

- Ali Ajikko

- A. Aima Musthafa

- Maisha Shareef Yoosuf

- Ismail Maaish Mohamed

- Mariyam Izza Moosa

- Mariyam Shany Ahmed (Manje)

- Aminath Ula Ahmed

- Aminath Shareehan Ibrahim

& Xavier Romero-Frias

The information in our exhibition is based on the research of Xavier Romero-Frias in his publications —

- Folk Tales of the Maldives (2012)

- The Maldive Islanders: A Study Of The Popular Culture Of An Ancient Ocean Kingdom (1999)

A note from Xavier Romero-Frias for Heritage Through Folk, 2018.

"I was 25 years old when I arrived in Maldives in the year 1979. The country seemed very quiet after Colombo. I couldn't talk to most Maldivians. Few back then knew English. I immersed myself in the society and immediately took steps to learn the language. Only a couple of weeks after my arrival in Male' I was aboard a small boat bound to Fua Mulaku. The deck was packed with men, women and children; these were oceanic people used to such journeys. I wasn’t prepared though. We went southwards from one atoll to the other. When the sea was calm and the weather was fair it was a pleasure to be on board. But occasional squalls made me miserable. Coming from the Mediterranean area I wasn't used to the violence of the rain lashing the canvas in the night and the dreadful waves that lapped parts of the deck of the overloaded boat.

After eleven days we saw Fua Mulaku in the horizon. The weather was grey and windy. Happy, smiling island women were standing on the prow. They were arriving home. As we sailed along the shore to the anchorage I saw many people in bright dresses among the coconut trees right above the beach. A small dinghy brought me across the wave barrier to the beach. Lots of children immediately surrounded me. I had a letter that my first Maldivian friend, Said Abdullah, had given me. The small crowd brought me to a house shaded by trees. People were sitting outside. A woman walking with crutches got up and read the letter. She welcomed me and everyone was smiling. From that moment I was adopted into the family and I was never lonely.

My achievements on the preservation of the Maldivian heritage came naturally along as I observed and took notes while being with the people. I also liked to draw and often carried my paper and pencils with me. I asked about island life, the vegetation and fishing. As my language skills improved I inquired about the old times and listened to stories which took a very long time to tell.

Sometimes I met island people who wondered about me in return. One of the questions that they asked over and over was whether my mom and dad were still in this world and why was I not going to live near them. They were family people and naturally thought that it was only common sense to wish to live among loved ones.

And truly I was far from home, in a strange country and not among my own kind. If at that time I would have had the wisdom I have now, I would have gone back home to be near my family. But I lacked the necessary insight to take that decision back then and I foolishly stayed on, delving deeper and deeper into the hidden soul of Maldives. As years went by, I stopped considering the Maldives as a foreign place. My own blood is there, as my children and grandchildren live on.

Only many years later I came to know that the lack of good judgment referred to above is one of the characteristics of the artist.

“An artist is a person who lives in the triangle which remains after the angle which we may call common sense has been removed from this four-cornered world.” —Natsume Sōseki

I am glad that there are now young people realizing the importance of the task I took upon myself. From the onset I was aware of the transcendence of my venture but I wasn’t sure whether recognition by Maldivians would be during my lifetime.

Thank you Oevaali Art Shop for this opportunity and I regret not being able to be present for the occasion."

After eleven days we saw Fua Mulaku in the horizon. The weather was grey and windy. Happy, smiling island women were standing on the prow. They were arriving home. As we sailed along the shore to the anchorage I saw many people in bright dresses among the coconut trees right above the beach. A small dinghy brought me across the wave barrier to the beach. Lots of children immediately surrounded me. I had a letter that my first Maldivian friend, Said Abdullah, had given me. The small crowd brought me to a house shaded by trees. People were sitting outside. A woman walking with crutches got up and read the letter. She welcomed me and everyone was smiling. From that moment I was adopted into the family and I was never lonely.

My achievements on the preservation of the Maldivian heritage came naturally along as I observed and took notes while being with the people. I also liked to draw and often carried my paper and pencils with me. I asked about island life, the vegetation and fishing. As my language skills improved I inquired about the old times and listened to stories which took a very long time to tell.

Sometimes I met island people who wondered about me in return. One of the questions that they asked over and over was whether my mom and dad were still in this world and why was I not going to live near them. They were family people and naturally thought that it was only common sense to wish to live among loved ones.

And truly I was far from home, in a strange country and not among my own kind. If at that time I would have had the wisdom I have now, I would have gone back home to be near my family. But I lacked the necessary insight to take that decision back then and I foolishly stayed on, delving deeper and deeper into the hidden soul of Maldives. As years went by, I stopped considering the Maldives as a foreign place. My own blood is there, as my children and grandchildren live on.

Only many years later I came to know that the lack of good judgment referred to above is one of the characteristics of the artist.

“An artist is a person who lives in the triangle which remains after the angle which we may call common sense has been removed from this four-cornered world.” —Natsume Sōseki

I am glad that there are now young people realizing the importance of the task I took upon myself. From the onset I was aware of the transcendence of my venture but I wasn’t sure whether recognition by Maldivians would be during my lifetime.

Thank you Oevaali Art Shop for this opportunity and I regret not being able to be present for the occasion."

Origin.

Acrylics on Canvas, 60 x 80 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

The place where it began, arose, and is derived from.

The Children of the Sea

Stories as ancient as they are, never venture to the origins of the Maldivian islanders. Through hundreds and thousands of years; within the legends, myths and stories, in the accounts of foreign kings, religious scholars and shipwrecked travellers; it would seem that the Dhivehi islanders; the primordial children of the sea, were already there — living in their islands.

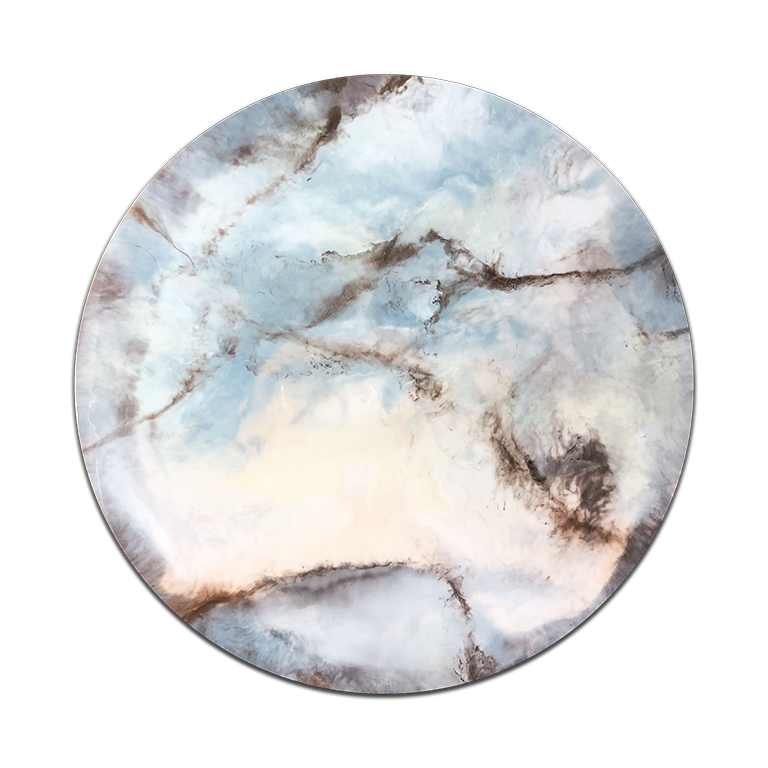

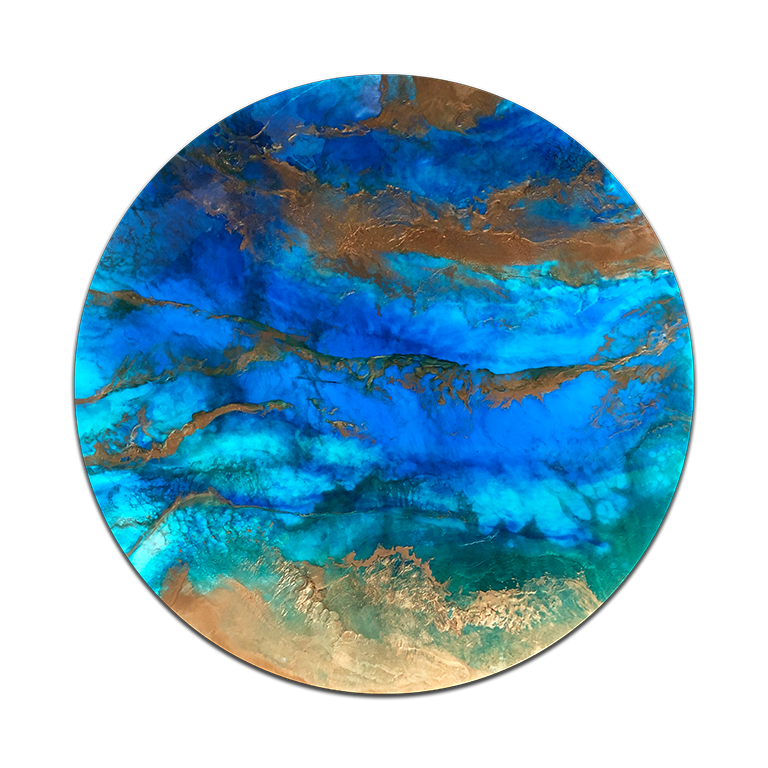

First Light.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Drawing from ancient beliefs of the old people, the mild shades of daybreak provokes calmness and peace of mind. This work symbolises the contentment, happiness and simplicity of the Maldivian islanders.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Drawing from ancient beliefs of the old people, the mild shades of daybreak provokes calmness and peace of mind. This work symbolises the contentment, happiness and simplicity of the Maldivian islanders.

Palms.

Acrylics on Canvas

80 x 60 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“After seeing too many islanders dying, a fanditha man prepared a secret magic mixture. Then he went to the graveyards and, before burial, he put a bit of that mixture in the mouth of every dead man, woman and child. During the following weeks the deaths continued unabated. But before long, out of the mouth of every buried skull a green shoot came out that grew into a young coconut palm. As time went by the trees began to develop.

Some were big, others small, some fairer and others darker, depending on the colour and size of the corpse from which they had originated.

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “The First Coconuts”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

80 x 60 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“After seeing too many islanders dying, a fanditha man prepared a secret magic mixture. Then he went to the graveyards and, before burial, he put a bit of that mixture in the mouth of every dead man, woman and child. During the following weeks the deaths continued unabated. But before long, out of the mouth of every buried skull a green shoot came out that grew into a young coconut palm. As time went by the trees began to develop.

Some were big, others small, some fairer and others darker, depending on the colour and size of the corpse from which they had originated.

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “The First Coconuts”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

A Symbol of Life

It is said that at childbirth, ancient Maldivians would find a soft, young coconut shell (kihah) and delicately place the placenta inside, after which it would be buried on the island with a coconut palm planted at the same spot. And so the islanders had growing, along the length of their lives, a palm which was planted at the moment they were born.

By oral tradition, the Maldive palms rose from the islanders themselves. The coconut is believed to resemble a skull, with two hard spots for the eyes and the softer opening for the mouth, from which a new palm will grow. In the Dhivehi language, the same word nāsi refer to the human skull, as well as the coconut shell. It is believed that the varying shades of skin in the islands correlate with the different cycles of the coconut, and are named as so.

Today the silhouette of the palm represents Maldivian nationalism, and the palm, with eleven fronds is centralized in the Maldivian national emblem.

By oral tradition, the Maldive palms rose from the islanders themselves. The coconut is believed to resemble a skull, with two hard spots for the eyes and the softer opening for the mouth, from which a new palm will grow. In the Dhivehi language, the same word nāsi refer to the human skull, as well as the coconut shell. It is believed that the varying shades of skin in the islands correlate with the different cycles of the coconut, and are named as so.

Today the silhouette of the palm represents Maldivian nationalism, and the palm, with eleven fronds is centralized in the Maldivian national emblem.

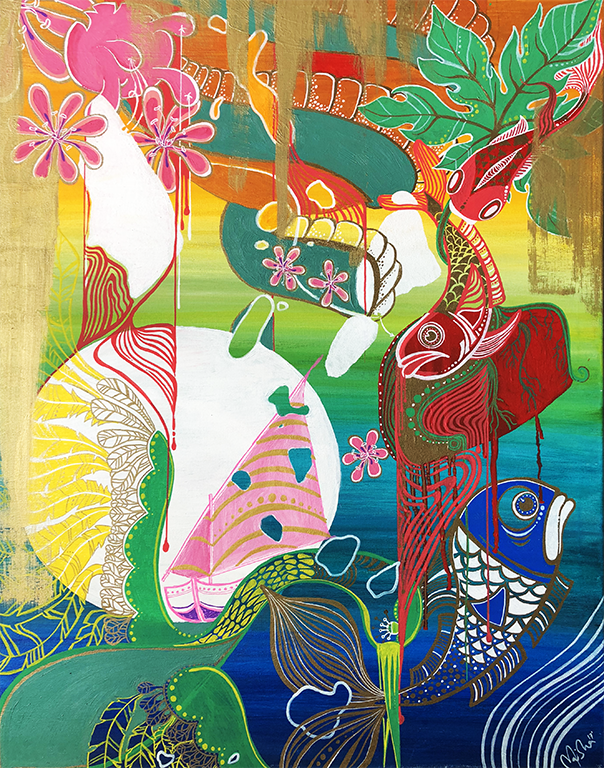

'Jan'gayyah Maleh Fadha Koi'.

Acrylics & Paint Markers on Canvas, 90 x 60 cm

Maisha Shareef Yoosuf, 2018

Translated as “The boy like a flower in the jungle”, this piece illustrates the lesser known background of Koimala Siri Mahaabarana Mahaa Radun; the first King of the Maldive islands. The highlights touch upon the Luna Dynasty; the extraordinary wonders he had seen during his early years that lead him to the Maldive Islands, and the tribe of Giraavaru he had encountered.

From the Maldives archipelago that is subtly scattered across the painting, Raa Atoll - Rasgetheem, Alhugetheem) and Kaafu Atoll (Male’ in particular) is given emphasis as they are significant areas that he resided on his conquest.

The red flesh patterns signifies the blood shed described in alternate narratives of the same story.

Based on the Legend of Koimala.

The Legend of Koimala

The legend of Koimala is an old story retold many times in different ways, and marks a turning point in the Maldivian civilisation.

It is said that Koimala's ship was guided by a magnificent white bird, to the islet we now know as Dūnidū. Close by was a sandbank, where the native fishermen of Girāvaru would cut and cook their fish, staining the surrounding beach and lagoons red with blood; giving meaning to it's appropriate name - Mahalē. It was here that Koimala encountered the oldest known tribe of the archipelago - the Girāvaru people - a free-spirited community, leading simple island lives sustained by fishing.

Koimala is believed to have built the first house in Mahalē. He planted a papaya tree - the first tree to grow on the island. This island is now know as Māle’, the capital of the Maldives.

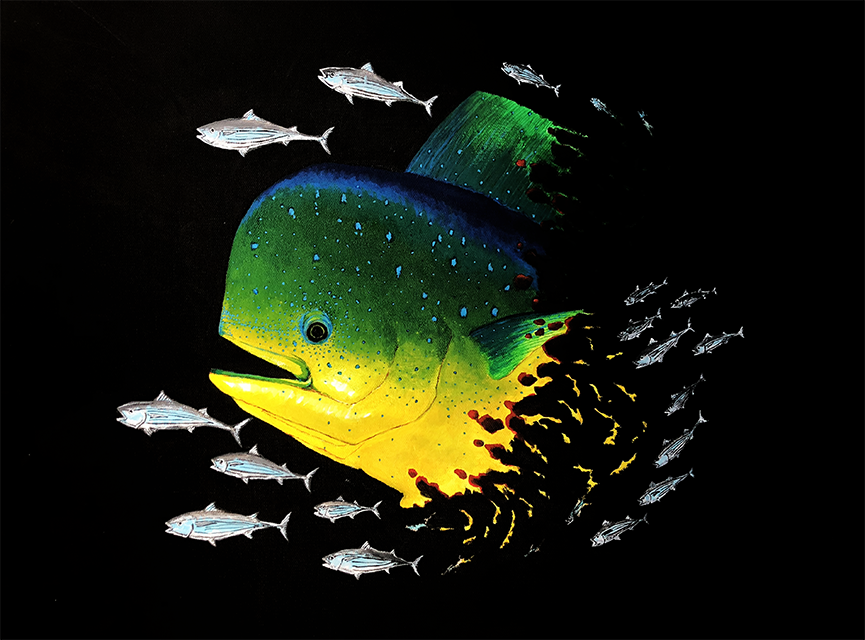

‘Fiyala Bo’ — Head of the Mahi-Mahi.

Acrylics on Canvas

45 x 60 cm

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Portrays how the head of a ‘fiyala’ (Mahi-Mahi) lead to the discovery of Skip Jack tunas by Maldivian fishermen.

The Edge of the World

Thousands of years ago in the island of Feridū in Ari Atoll, a famous mālimi (navigator) known as Bodu Niyami Takurufānu went on a voyage out at sea. His boatmen were fishing and caught great big fiyala (Mahi-Mahi). The head of the fiyala is delicious, and Bodu Niyama ordered his men to keep the head of the fish for him. When he realized later that one of his men had not only picked clean the head of the fiyala, but also thrown it to the sea, he flew into an irrational rage, and ordered the helmsman to sail towards the head of the fiyala.

And so they sailed, it is said, for eighty eight days until finally they reached the edge of the world. A surreal looking enderi (black coral) rose above the ocean like a majestic black tree, and strong currents of water dropped down to infinity over the edge beyond it. A big and peculiar fish leapt around the waters around the black tree. The navigator traced the shape of the fish on a piece of parchment, rolled it into his bamboo flask and whispered a magical chant. As the ship made it's way back to the Maldivian islands, so did the tunas, in large schools trailing the boat, and there they settled into the blue depths of the Maldivian oceans.

This ancient lore is the myth of the first tunas; and since the day the ship returned to the Maldives, there have always been schools of tuna in our seas. Considered the "King of the Fishes", Skip Jack Tuna (kalhubilamas) is now known as the Maldive Fish and continues to be a preferred staple on any Maldivian dining table.

Hidden Creatures.

Acrylics & Inks on Paper,

42 x 30 cm

42 x 30 cm

Mariyam Izza Moosa, 2018

A simple tale of the Man on a Whale. Greens resembles the seaweed-like legs of the man. Blues paint the ocean. Gold represents the whale, and this unique tale.

“Maldivians say that there is a man living in the middle of the ocean. The man on the whale has been living already for so long in the water that you almost can’t see the skin of the lower part of his body. From the waist downwards, he is covered with barnacles and seaweed.”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Man on the Whale”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Man on the Whale”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

A Pattern of Powers

Dhivehi Madulu, or the Mandala corresponds with the geographical cardinal points known in old Dhivehi as the Uttara (N), Dakusana (S), Fūrubba (E) and Fakusama (W).

Mandalas represent a universe or a microcosm of the universe, perfectly connecting every element from the edge to the core.

In a landscape dominated by the sea, and a seafaring people within it, being correctly oriented is of utmost importance. Creating order out of chaos was essential. Without accurate mapping, ancient islanders perceived themselves living in a great Mandala - a calm inner eterevaru lagoon, with their islands safely within. Beyond lies the futtaru, an unpredictable open sea.

Natural atolls such as Miladummadulu, Malosmadulu and Kolumadulu carry the word Madulu (Mandala) in their very names, mystifying the science of geography altogether.

'Kai'dha'.

Watercolour, Gauche & Inks on Paper

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Aminath Ula Ahmed, 2018

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Aminath Ula Ahmed, 2018

‘Finolhu’— Sandbank.

Acrylics & Marker on Canvas 3 panels

90 x 60 cm

A. Aima Mustafa, 2018

A secluded safe haven for the seabirds, a sandbank is lost forever with the arrival of a visitor. An important reminder to always consider advice from the old and the wise. The three pieces, each with its own hidden element, shows time as a sequence of events.

90 x 60 cm

A. Aima Mustafa, 2018

A secluded safe haven for the seabirds, a sandbank is lost forever with the arrival of a visitor. An important reminder to always consider advice from the old and the wise. The three pieces, each with its own hidden element, shows time as a sequence of events.

A Delicate Balance

Harmony was paramount in the island life. Change was feared and mistrusted. Suspicion was justified towards one who might appear to upset the delicate balance.

Islanders were indignant and disgruntled by the unfamiliar visitors, or outside influences. It was a matter for alarm and worry, and a dreadful anticipation of an impending danger, or an incredible foresight for such a danger in the far-future.

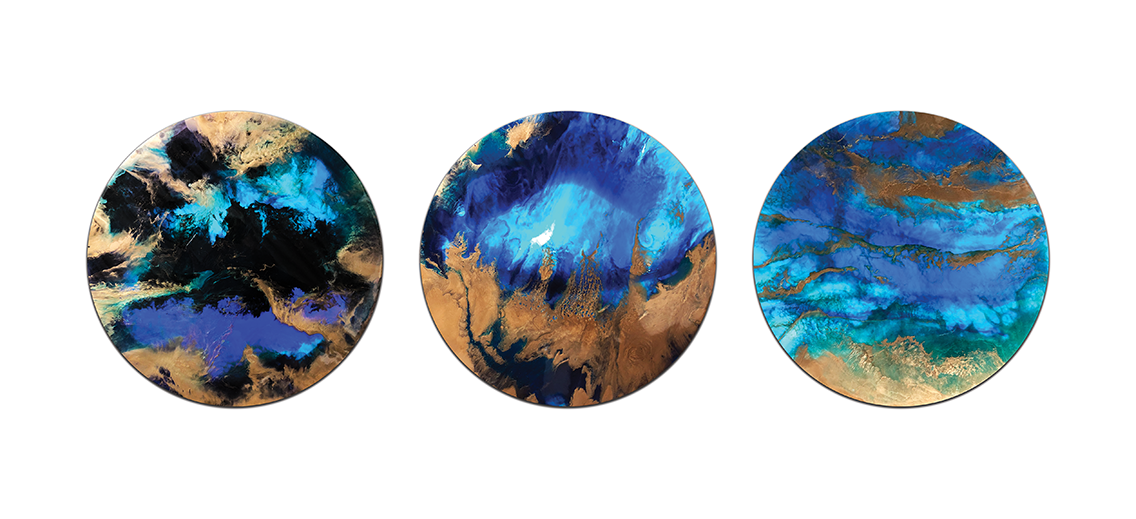

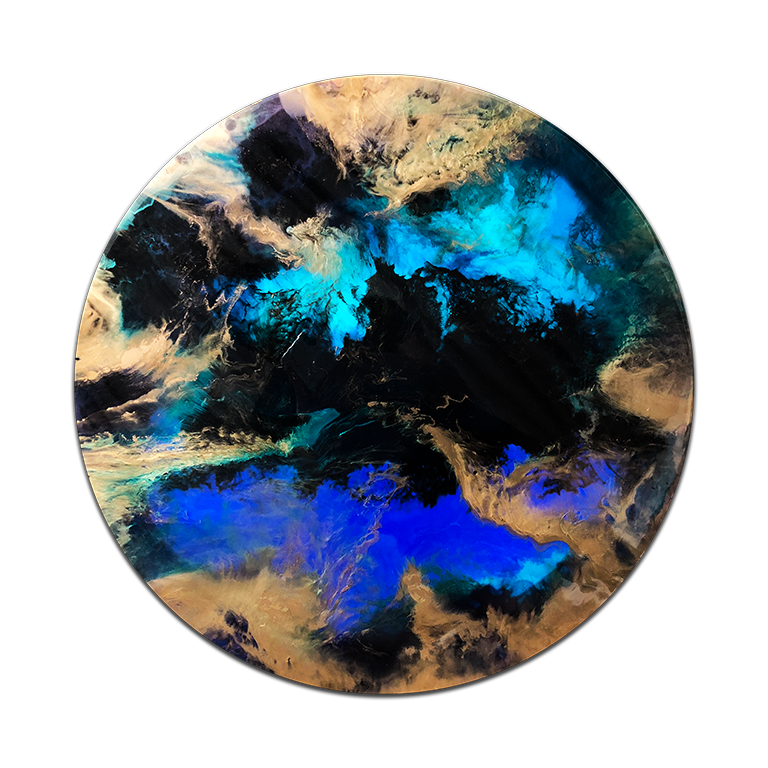

Circle of Magic — ‘Ana’

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Drawn from the ancient practices of Fanditha sorcery, the circle of magic known as “Ana” symbolise protection, and strength within. The three pieces show magic overcoming the darkness, and restoring calm.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Drawn from the ancient practices of Fanditha sorcery, the circle of magic known as “Ana” symbolise protection, and strength within. The three pieces show magic overcoming the darkness, and restoring calm.

Rituals

The Masdayffiohi ritual knife has a distinctive sperm whale tooth handle, and a blade of seven metals - a powerful weapon in rites and rituals against evil spirits and demons. As Maldivians did not hunt sperm whales, such genuine ritual knives were difficult to find or craft; the islanders would use teeth from dead whales that occasionally drifted to their beaches.

The knife was, and still is used alongside recitations to draw magical protective circles or ana; thrust to the ground or tree stumps with force to banish or control spirits; or used to write magical scripts on wood or leaves.

The knife was, and still is used alongside recitations to draw magical protective circles or ana; thrust to the ground or tree stumps with force to banish or control spirits; or used to write magical scripts on wood or leaves.

The Evil Hour

Dusk to dawn was a time to be indoors, especially for children and expecting mothers. The red sky at sunset represented the evil hour; and was considered ill-fated. Red skies, and the reflecting red waters at the evil hour was connected with malevolence, and was in all possible ways, avoided. Children were promptly brought indoors, and even children's clothes drying outdoors would be removed.

Stories such as Kalobolā, and the Safaru Kaiddā - spirits lurking in the dark night - were told by mothers and fathers in dimly lit rooms in the evening to warn children to not step out once the sun starts coming down.

Stories such as Kalobolā, and the Safaru Kaiddā - spirits lurking in the dark night - were told by mothers and fathers in dimly lit rooms in the evening to warn children to not step out once the sun starts coming down.

‘Kandu’guruvaa Noonee Nukaanan’.

Inks on Paper

40 x 30 cm Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed, 2018

Days passed and the bird weakened, but his stubbornness kept him going. The fish he wanted was not getting any closer. He could see its tantalizing shape in the depths before him. The kanduguruva never came close to the surface. Finally the maakanaa got so exhausted, and he died on the spot. He never got what he wanted, but he had never given up.

40 x 30 cm Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed, 2018

Days passed and the bird weakened, but his stubbornness kept him going. The fish he wanted was not getting any closer. He could see its tantalizing shape in the depths before him. The kanduguruva never came close to the surface. Finally the maakanaa got so exhausted, and he died on the spot. He never got what he wanted, but he had never given up.

The Dakō

The danger that an outbreak of illness may wipe out an entire island terrified the ancient Maldivian islanders. Lethal and sudden illnesses struck the islands periodically, causing distress and suffering. The island sorcerer or the fanditaveriyā would be sought to ward off the affliction with elaborate rituals and save the island.

Fever, boils and death were attributed to the Vigani, an amorphous evil, living inside of sick men and women, and consequently, they would be made to live far, far away from the village, within the forest or the beach. Fear ruled over mercy and compassion.

Among the spirits within the island, it is believed that the dakō appeared when the diseases of the Vigani spreads on the island. In Southern Maldives, the dakō is believed to be the companion of the Vigani, as it comes along with it.

Fever, boils and death were attributed to the Vigani, an amorphous evil, living inside of sick men and women, and consequently, they would be made to live far, far away from the village, within the forest or the beach. Fear ruled over mercy and compassion.

Among the spirits within the island, it is believed that the dakō appeared when the diseases of the Vigani spreads on the island. In Southern Maldives, the dakō is believed to be the companion of the Vigani, as it comes along with it.

‘Bibi’

Inks on Paper

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed

This work illustrates the story of a mother’s long journey from Baa. Dharavandhoo to Haa. Alif. Kelaa to save her 40 children from a sudden illness.

On this voyage, many of her children died. To smother the scent of death, Bibi filled up the dhoni with sweet dhonkashikeyo (screw pines) from a nearby island, Baa. Mudhoo. To this day, even the sweetest of dhonkashikeyo from the island of Baa. Mudhoo are odourless.

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed

This work illustrates the story of a mother’s long journey from Baa. Dharavandhoo to Haa. Alif. Kelaa to save her 40 children from a sudden illness.

On this voyage, many of her children died. To smother the scent of death, Bibi filled up the dhoni with sweet dhonkashikeyo (screw pines) from a nearby island, Baa. Mudhoo. To this day, even the sweetest of dhonkashikeyo from the island of Baa. Mudhoo are odourless.

The Ocean & The Woman

The ambivalence within the Dhivehi woman, and the surrounding ocean is a recurring theme. A beautiful woman and nurturing mother could be provoked to become a vicious, fearsome and powerful terror. A nourishing and bountiful ocean could quickly be a vast, dark, haunting and dangerous place.

The Dhivehi woman, and the Maldivian seas are double-edged swords in folklore, and possibly the most feared aspects of ancestral Maldivian island life.

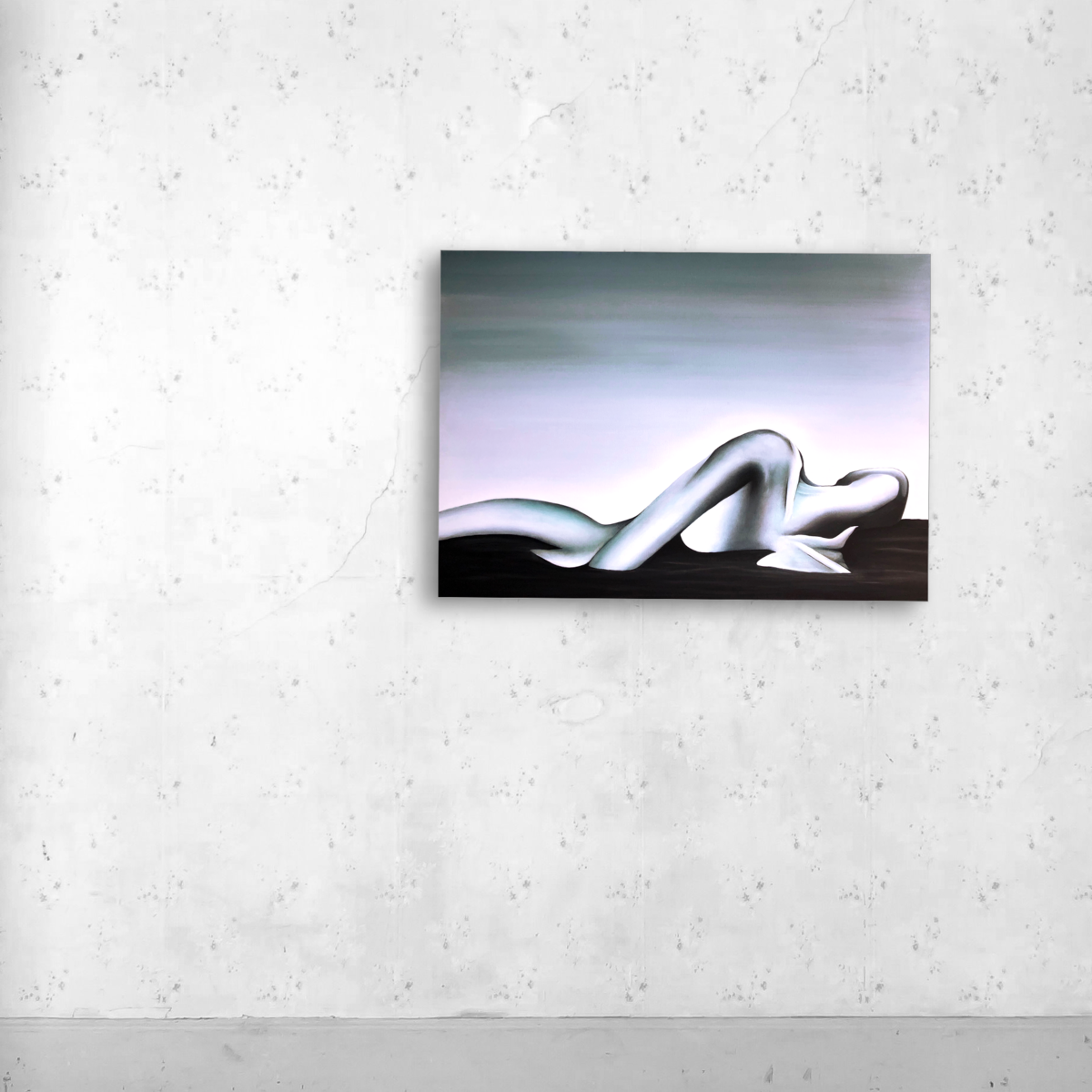

With the Sea.

Acrylics on Canvas

60 x 80 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

"...she gradually became accustomed to the night and she learned to walk to the beach in the starlight and not fear looking at the dim sea. Watching the white, frothy foam of the waves breaking against the coral reef protecting the island suited her mood and fed her soul”.

A story about finding comfort in the sea.

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Havva Didi”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

60 x 80 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

"...she gradually became accustomed to the night and she learned to walk to the beach in the starlight and not fear looking at the dim sea. Watching the white, frothy foam of the waves breaking against the coral reef protecting the island suited her mood and fed her soul”.

A story about finding comfort in the sea.

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Havva Didi”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

‘Hiyalā’

Watercolour & Inks on Paper

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed, 2018

This work is inspired by how Don Hiyalā and Alifuļu fell in love, spending the day and night in total bliss, unaware of impending tragedy.

40 x 30 cm, Framed

Ismail Maaish Mohamed, 2018

This work is inspired by how Don Hiyalā and Alifuļu fell in love, spending the day and night in total bliss, unaware of impending tragedy.

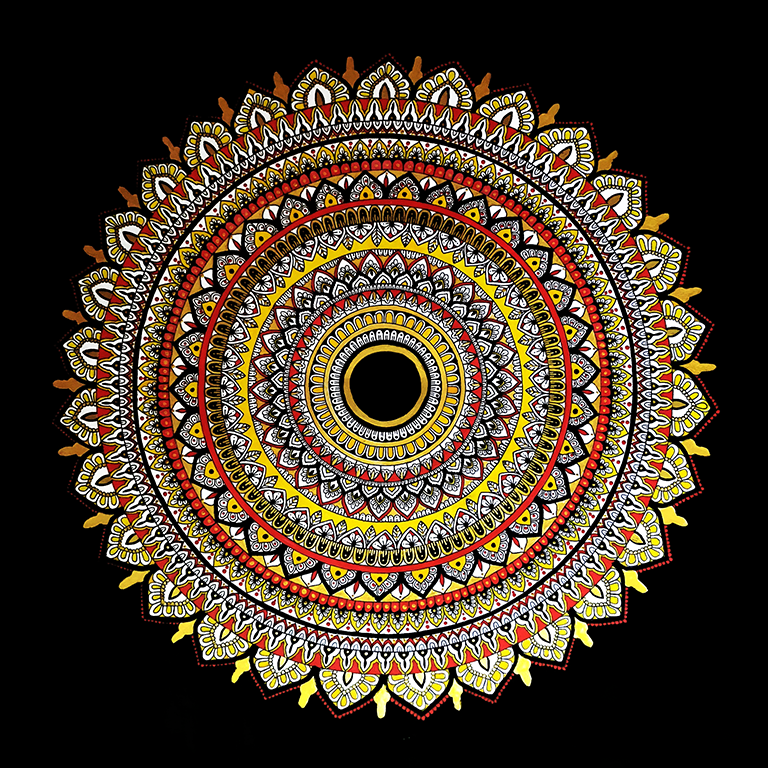

Fragments of Greed.

Acrylics & Inks on Paper,

42 x 30 cm, Framed

Mariyam Izza Moosa, 2018

Inspired by the folk story “Fruits of Greed”, the colours represent the essence of the story. The mandala represents the coins and the handi, both crucial elements of the narrative. Gold detailing represents the coins. Red, black and gold represent the handi, who has black hair, and wears the traditional red libaas with gold jewelry. A black background stands for the dark consequences of greed.

42 x 30 cm, Framed

Mariyam Izza Moosa, 2018

Inspired by the folk story “Fruits of Greed”, the colours represent the essence of the story. The mandala represents the coins and the handi, both crucial elements of the narrative. Gold detailing represents the coins. Red, black and gold represent the handi, who has black hair, and wears the traditional red libaas with gold jewelry. A black background stands for the dark consequences of greed.

The Sin of Greed

In the Maldivian traditional wisdom, the worst sins of a man or woman are greed and arrogance. Many tales told and retold highlight the dangers of greed and arrogance, and the outcomes of behaving like so usually would lead one to ruin and despair.

The story “Fruits of Greed” tells the tale of Kayddā & Maniku, who meet a beautiful woman in the forest. Upon seeing them wailing in despair over the poverty of their family, she provides them with a few gold coins. Kayddā & Maniku take the strange woman’s gift, and as she advised, built a small fishing boat. Eventually, their family begins to live a happy and contented life without struggle. However, greed convinces them to go back to the forest for more gold coins, leading them to face the wrath of the woman of the forest, who was no longer beautiful nor kind as she had been before.

“All of a sudden a monstrous being appeared in front of them and they held each other in terror. It was not the lovely girl they had expected, but a hideous-looking woman. Her face was too horrible to behold, with a wide mouth full of huge sharp teeth, a wild mane of hair and hands with long nails, stained with blood. She looked cruelly at them with bloodshot eyes and spoke with a roaring voice, “Why did you come here again? Did I tell you to come?”

The frightened couple didn’t dare to utter a word. Instead, they turned around in panic and fled as fast as they could. When Kayddā and Maniku arrived home, they were panting and shivering. The very next day, while Maniku was out fishing, his sailboat crashed against a hidden coral reef and sank. He barely managed to save himself and came back home with only the clothes he wore. After this he and his wife Kayddā became again a poor wretched couple. They lived as miserably as they had been living before.”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “The Fruits of Greed”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

The story “Fruits of Greed” tells the tale of Kayddā & Maniku, who meet a beautiful woman in the forest. Upon seeing them wailing in despair over the poverty of their family, she provides them with a few gold coins. Kayddā & Maniku take the strange woman’s gift, and as she advised, built a small fishing boat. Eventually, their family begins to live a happy and contented life without struggle. However, greed convinces them to go back to the forest for more gold coins, leading them to face the wrath of the woman of the forest, who was no longer beautiful nor kind as she had been before.

“All of a sudden a monstrous being appeared in front of them and they held each other in terror. It was not the lovely girl they had expected, but a hideous-looking woman. Her face was too horrible to behold, with a wide mouth full of huge sharp teeth, a wild mane of hair and hands with long nails, stained with blood. She looked cruelly at them with bloodshot eyes and spoke with a roaring voice, “Why did you come here again? Did I tell you to come?”

The frightened couple didn’t dare to utter a word. Instead, they turned around in panic and fled as fast as they could. When Kayddā and Maniku arrived home, they were panting and shivering. The very next day, while Maniku was out fishing, his sailboat crashed against a hidden coral reef and sank. He barely managed to save himself and came back home with only the clothes he wore. After this he and his wife Kayddā became again a poor wretched couple. They lived as miserably as they had been living before.”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “The Fruits of Greed”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

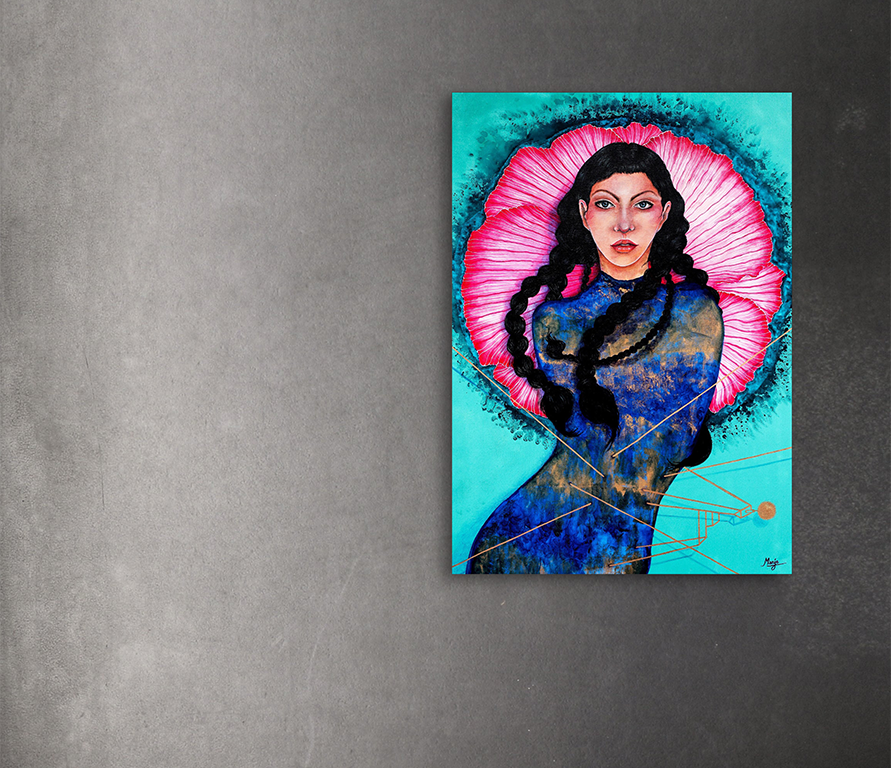

Love for Gold

Acrylics & Gold Leaf Ink on Canvas, 100 x 70 cm

Mariyam Shany Ahmed (Manje)

Illustrates the story of a beautiful spirit who gave a poor couple gold coins to help them get by. The couple overtime became greedy and went against their vow to the spirit. The artwork shows a young pleasant woman painted with accents of gold leaf paint on and around her, and a hibiscus behind her.

Kalobolā

It is said that in the darkness of long Maldivian nights, a regal-looking female spirit, whose skin is the colour of the deep ocean makes a stately entrance in her own splendor. Her permanent companion, Haiybōrāhi; the seven-headed snake looms behind her like a blue shadow, and attending to her are her seven daughters.

Believed to be a manifestation of the Hāmundi, this spirit causes fear in children. Perched atop the thatched roof huts, her mere presence ignites cold fright in the hearts of children and continuous crying follows her wake through the village.

Crying children was considered unusual in the Maldive islands. When a child wept, the islanders react immediately to still the child; using bananas and sweets; or simple silliness. Continuous crying was an ill omen, and believed to be a result of a pernicious spirit that if the child was not stilled soon, more evil would ensue and eventually lead to illness and death. Powerful magic in the form of fanditha was done against such spirits and demons.

The story of Kalobolā ('black head') describes a terrifying encounter, often retold in the bandhi form of verse, and tells the tale of the night-spirit whisking away a crying boy eastwards, from island to island in South Huvadu Atoll. In some versions of the story, the boy returns safely after an adventure; in more disturbing versions he returns with one eye plucked out, or he does not survive the journey at all.

Forest.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Within the groves and deep inside the woods is both a place of beauty and mystique. Painted in the colours of the trees and the low, golden sun, this work showcases the beautiful enigma that is the island forest.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Within the groves and deep inside the woods is both a place of beauty and mystique. Painted in the colours of the trees and the low, golden sun, this work showcases the beautiful enigma that is the island forest.

Women of the Forests

The forests of the islands were considered dangerous, particularly after the sun sets.

Beautiful women within the trees dominate many stories in Maldivian folklore - the Handi is a manifestation of female power. She emerges from the deepest depths of the forest when the sun is low, and the sky is golden. Her voice is eerily soothing and she might converse in alluring raivaru or Maldivian couplets; song. Her face shines like the moon, her body adorned with fine gold and copper jewelry. Deep red wild flowers decorate her long black hair as it flows in the wind. She can go from beauty, benevolence and pleasure, to fearsome, terror and grave harm in the blink of an eye.

A burning fever is the first symptom of her presence.

Beautiful women within the trees dominate many stories in Maldivian folklore - the Handi is a manifestation of female power. She emerges from the deepest depths of the forest when the sun is low, and the sky is golden. Her voice is eerily soothing and she might converse in alluring raivaru or Maldivian couplets; song. Her face shines like the moon, her body adorned with fine gold and copper jewelry. Deep red wild flowers decorate her long black hair as it flows in the wind. She can go from beauty, benevolence and pleasure, to fearsome, terror and grave harm in the blink of an eye.

A burning fever is the first symptom of her presence.

Handi.

Clay & Foam on Balsa Wood Base

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Represents the double face of femininity; from beauty to terror, gentle to powerful — the Handi.

The women of the island, like their matriarchal Dravidian ancestors, secured their own way. The gentle and equally powerful duals of women were appreciated and revered, and taken as a whole.

This is symbolised by their daunting role within the core of Maldivian mythology.

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Represents the double face of femininity; from beauty to terror, gentle to powerful — the Handi.

The women of the island, like their matriarchal Dravidian ancestors, secured their own way. The gentle and equally powerful duals of women were appreciated and revered, and taken as a whole.

This is symbolised by their daunting role within the core of Maldivian mythology.

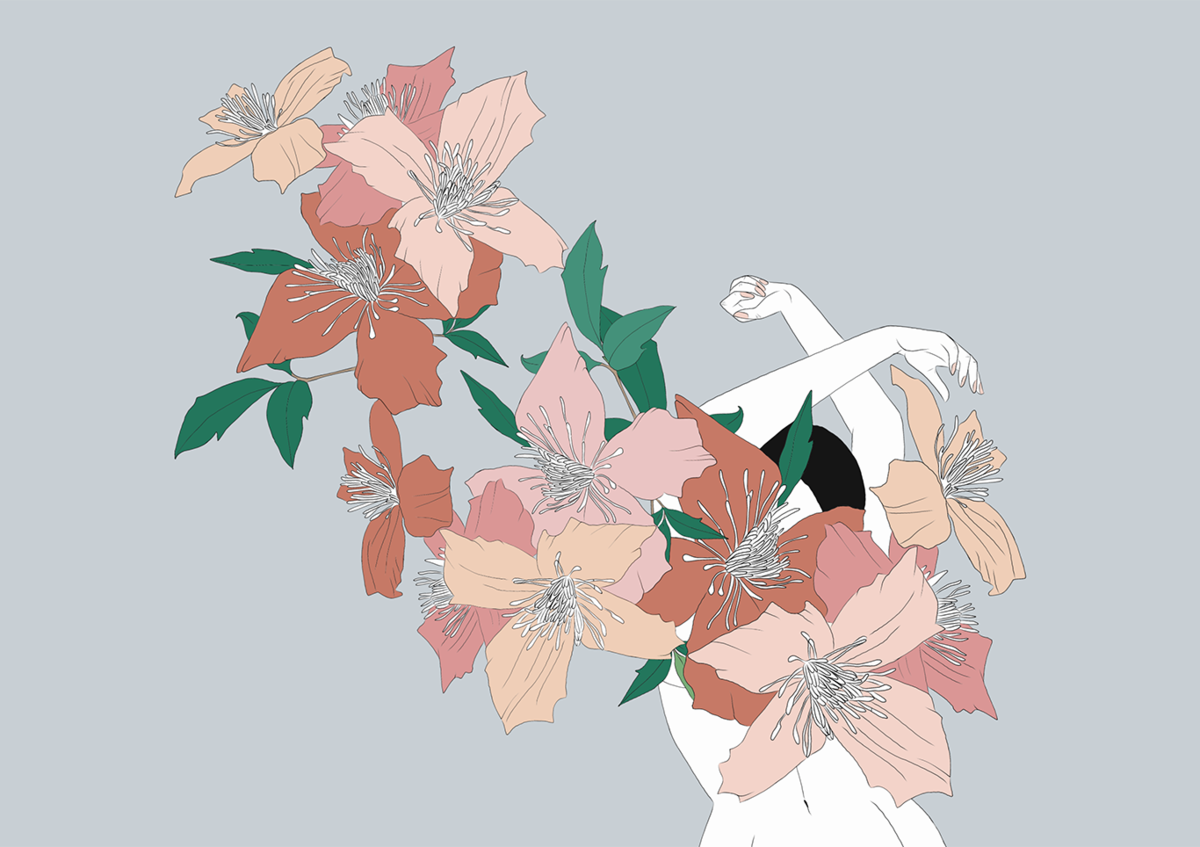

Flora.

Digital Illustration; Canvas Print, 30 x 40 cm

Raniya Mansoor, 2018

She is freedom — to live in wilderness; to roam her islands, to love. She is free of society. She needs no consort — she protects herself.

Based on Handi; the female spirit of the forests.

Raniya Mansoor, 2018

She is freedom — to live in wilderness; to roam her islands, to love. She is free of society. She needs no consort — she protects herself.

Based on Handi; the female spirit of the forests.

Hidden Villages

The waves crashing at the shore, followed a narrow and winding path to the village huts. The deeply feared Vigani, and the frightening Kaddovi; spirits of the dead, were believed to move in straight lines.

Villages were built with a deeper purpose, than simply following a sociological plan - sanctifying spaces was essential.

Villages were built with a deeper purpose, than simply following a sociological plan - sanctifying spaces was essential.

The Spirit of the Sea

Acrylics on Canvas, 80 x 60 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“Long ago on Fua Mulaku Island’s western edge, where a village path joins the beach at a place called Arruffanno, a monster came ashore from the sea. Fearing that the monster could make the island deserted, the fanditha man Edurutakkānge Muhammad Dīdī casted a powerful spell that turned the monster into a coral rock.

This rock can still be seen at Arruffanno in the western shore of Fua Mulaku. There the reef surface is flat and that isolated rock stands out in the landscape”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; ”Arrufanno Ferēta”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“Long ago on Fua Mulaku Island’s western edge, where a village path joins the beach at a place called Arruffanno, a monster came ashore from the sea. Fearing that the monster could make the island deserted, the fanditha man Edurutakkānge Muhammad Dīdī casted a powerful spell that turned the monster into a coral rock.

This rock can still be seen at Arruffanno in the western shore of Fua Mulaku. There the reef surface is flat and that isolated rock stands out in the landscape”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; ”Arrufanno Ferēta”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

Kandumathi.

Acrylics on Canvas, 60 x 80 cm

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Based on a haunting at sea.

“Kollaa,

Oevaru the’reyn e araa vigan’yaa

Han’dhuvaru mathee emburey gaburakaa

Biya bainyakun leggi mai’yithaa...”

— Lyrics from the song “Kandu’mathi Elhy” by Andhalaa Haleem.

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Based on a haunting at sea.

“Kollaa,

Oevaru the’reyn e araa vigan’yaa

Han’dhuvaru mathee emburey gaburakaa

Biya bainyakun leggi mai’yithaa...”

— Lyrics from the song “Kandu’mathi Elhy” by Andhalaa Haleem.

Saangu Boli.

The Trident Conch holds an important place in Maldivian culture as a tool of heraldry.

It has roots in our Dravidian heritage.

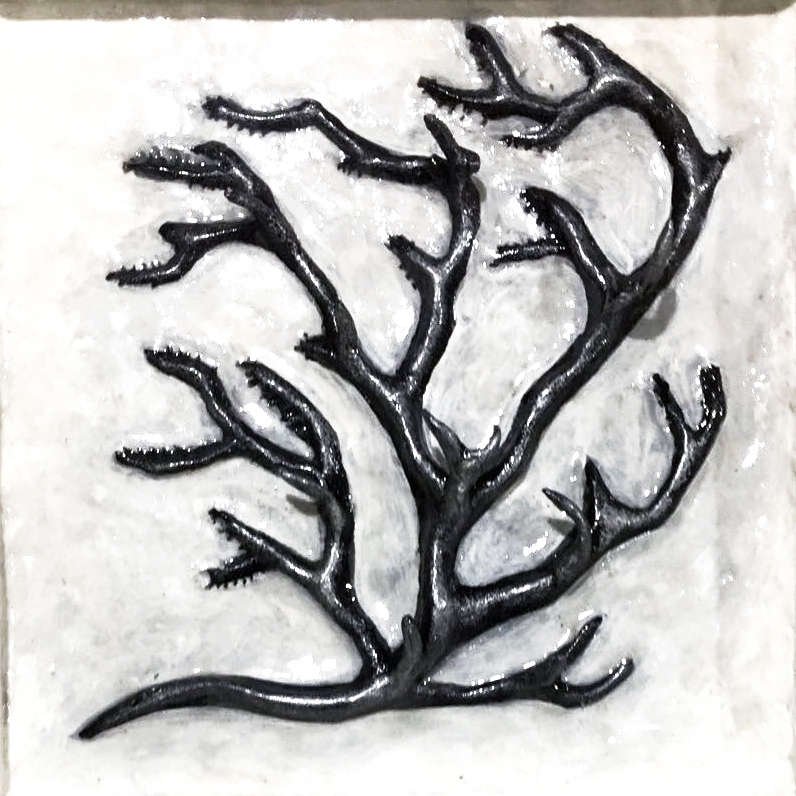

Enderi.

The black coral holds a special place in Maldivian folklore.

It is said to be the tree at the end of the world.

Naru Nagoo Madi.

Inspired by the story of the boy who got stung by a stingray. Though the story specified a Blue Spotted Ribbontail Ray, I used a Jenkins’ Whipray because of the terrifyingly beautiful whiptail.

Femunu.

Clay & Acrylics with Varnish Finish 25 x 25 cm, Framed

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Imma Rasheed, 2018

Tiger Sharks were hunted for their liver oil that was used to make resin for traditional Dhonis. Giant sharks also appear in many folk stories. Significant among them, the story of the girl who was swallowed whole by a shark.

Bēri

This is a story set in Kandûdû Island, on the southern rim of Miladummadulu Atoll, a thriving and populous island - once upon a time.

A young woman was resting on a dark log of wood that had drifted upon the beach, and could not help reliving her lascivious secret dreams by the sea. She returns to the same log time and time again, with lust in her heart and the ocean beneath her feet. The log, one evening, becomes a man - a tall, dark, and strong Maldivian fantasy. The man walked resolutely to the Island Chief’s house, finds the door open and enters the threshold. The Island Chief’s daughter finds him in the lamp-lit veranda of her house, with windswept hair and dark glistening skin. He only looks at her, and she is captivated. They had a beautiful, ravenous, passionate love and lived together in happiness.

Like her dream sadly, it was short lived, for the island sorcerer had long suspected that the Island Chief’s new son-in-law was not quite human, but a Bēri - a spirit from the sea. With powerful magic, the sorcerer shunned the man from the island, and his devastated wife longed for her lover from the sea, until the day she died.

They say the reason why Kandûdû Island is deserted is because the Bēri returned with anger, and haunted the islanders. No one lives there anymore.

A young woman was resting on a dark log of wood that had drifted upon the beach, and could not help reliving her lascivious secret dreams by the sea. She returns to the same log time and time again, with lust in her heart and the ocean beneath her feet. The log, one evening, becomes a man - a tall, dark, and strong Maldivian fantasy. The man walked resolutely to the Island Chief’s house, finds the door open and enters the threshold. The Island Chief’s daughter finds him in the lamp-lit veranda of her house, with windswept hair and dark glistening skin. He only looks at her, and she is captivated. They had a beautiful, ravenous, passionate love and lived together in happiness.

Like her dream sadly, it was short lived, for the island sorcerer had long suspected that the Island Chief’s new son-in-law was not quite human, but a Bēri - a spirit from the sea. With powerful magic, the sorcerer shunned the man from the island, and his devastated wife longed for her lover from the sea, until the day she died.

They say the reason why Kandûdû Island is deserted is because the Bēri returned with anger, and haunted the islanders. No one lives there anymore.

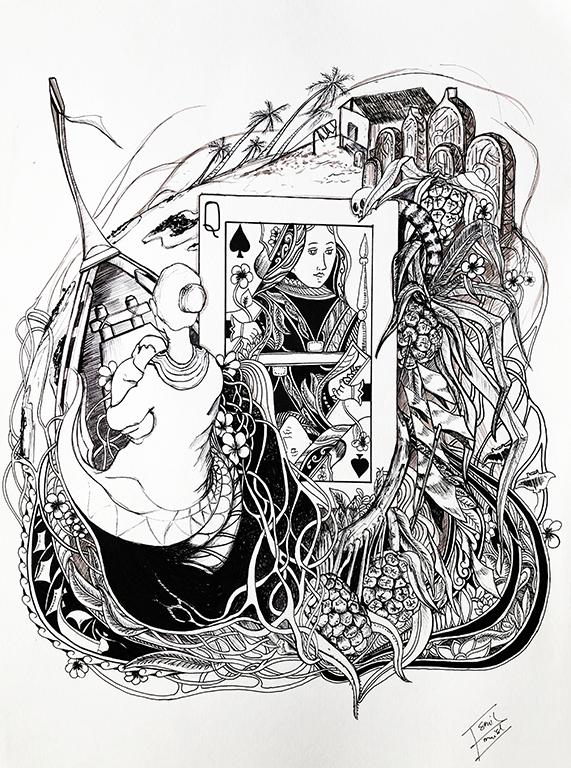

Sex Dream.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Sultry, sensual and deep mulberry hues paint the secret dreams and desires of the Island Chief’s daughter.

Based on the story ‘Bēri’ & ‘Leggi Lakudi’.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Sultry, sensual and deep mulberry hues paint the secret dreams and desires of the Island Chief’s daughter.

Based on the story ‘Bēri’ & ‘Leggi Lakudi’.

Lustre.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

Based on the tale of ‘The White Disk’, this work portrays the ability to overcome sadness and embracing your own light.

Three Waves.

Acrylics on Canvas

100 x 120 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“Oditan Kalege stayed awake at night and watched what his wife does, on the dark nights of the new moon. Seeing his wife becoming a monster at night, Oditān Kalēge decided that he had to stop Dōgi Āihā’s bloodshed there and then.

Thus, without wasting more time, the sorcerer gathered firewood, built a fire close to her.

Furious at seeing him, Dōgi Āihā Kālēge thrust her right hand forward, raised three huge waves of fire from the sea, and hurled them after him. The massive effort left her exhausted. Instantly she died. Meanwhile Oditān Kalēge saw the three flaming waves fast approaching him. Being near an islet, he hastily made for its beach. The moment he stepped on the sand, he was beyond their reach. Hence, they turned into waves of water, and so he was saved.

To this day, at a point near the beach of Golā Konā in Haddummati Atoll, ocean swells break constantly into series of three waves. Natives of the atoll attribute this natural wonder to Dōgi Āihā Kālēge. They say that her magic fire waves became normal ones and stayed there forever.”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Oditān Kalēge and His Wife”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

100 x 120 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“Oditan Kalege stayed awake at night and watched what his wife does, on the dark nights of the new moon. Seeing his wife becoming a monster at night, Oditān Kalēge decided that he had to stop Dōgi Āihā’s bloodshed there and then.

Thus, without wasting more time, the sorcerer gathered firewood, built a fire close to her.

Furious at seeing him, Dōgi Āihā Kālēge thrust her right hand forward, raised three huge waves of fire from the sea, and hurled them after him. The massive effort left her exhausted. Instantly she died. Meanwhile Oditān Kalēge saw the three flaming waves fast approaching him. Being near an islet, he hastily made for its beach. The moment he stepped on the sand, he was beyond their reach. Hence, they turned into waves of water, and so he was saved.

To this day, at a point near the beach of Golā Konā in Haddummati Atoll, ocean swells break constantly into series of three waves. Natives of the atoll attribute this natural wonder to Dōgi Āihā Kālēge. They say that her magic fire waves became normal ones and stayed there forever.”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Oditān Kalēge and His Wife”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

The Dagas.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko 2018

This painting is an imaginative representation of the mythical land of the Dagas, as told in the story of the "Two Headed Bird".

It is said that upon seeing the cunningness of man, the majestic two-headed birds that once lived on the islands rose to the sky and flew higher and higher until they left the Earth and reached the Dagas, the tree that grows beyond the world.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko 2018

This painting is an imaginative representation of the mythical land of the Dagas, as told in the story of the "Two Headed Bird".

It is said that upon seeing the cunningness of man, the majestic two-headed birds that once lived on the islands rose to the sky and flew higher and higher until they left the Earth and reached the Dagas, the tree that grows beyond the world.

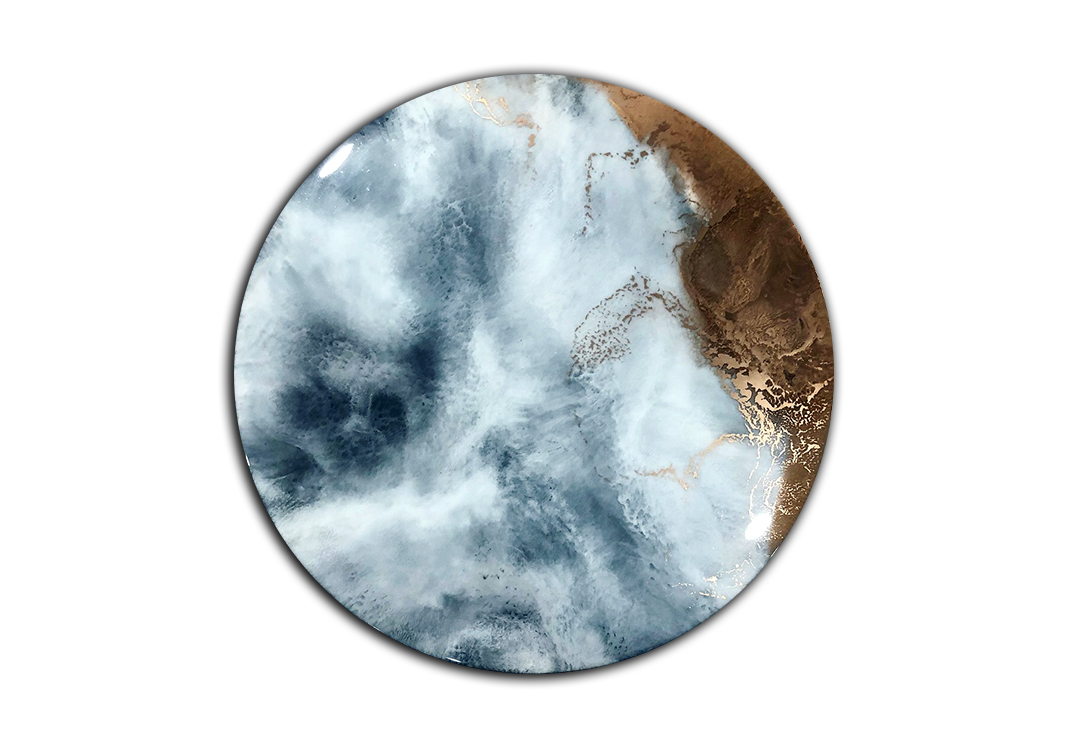

Eclipse.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko 2018

Astronomical and lunar events, and the tidal oceans and surreal skies that come alongside them were of superstitious significance to the islanders. This painting portrays the mystery of the moon.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko 2018

Astronomical and lunar events, and the tidal oceans and surreal skies that come alongside them were of superstitious significance to the islanders. This painting portrays the mystery of the moon.

Dhon Hiyala.

Acrylics on Canvas, 100 x 90 cm

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“She told Alifulhu, ‘I will rather die than let this cruel demon of a man take me away again!’ — And before Alifulhu could catch her, Don Hiyalā jumped into the ocean. Alifulhu also sank along with his Don Hiyalā’s body until they both were lost in the blue depths. Thus were the faithful loving couple reunited at last and no one would be able to separate them again”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Don Hiyalā & Alifulu”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

Raya Mansoor, 2018

“She told Alifulhu, ‘I will rather die than let this cruel demon of a man take me away again!’ — And before Alifulhu could catch her, Don Hiyalā jumped into the ocean. Alifulhu also sank along with his Don Hiyalā’s body until they both were lost in the blue depths. Thus were the faithful loving couple reunited at last and no one would be able to separate them again”

— Xavier Romero-Frias; “Don Hiyalā & Alifulu”; Folk Tales of the Maldives; 2012.

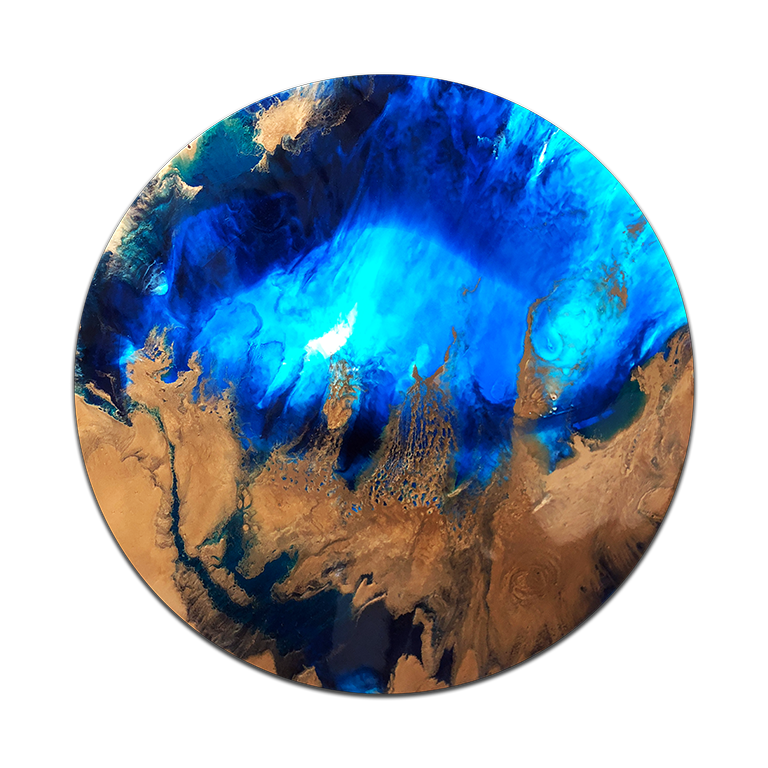

The Island.

Ink, Pigment Powders & Resin on Wooden Board, 60 cm

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

This work is nostalgic of how the Maldivians experienced life, as an organic whole - life, death, love, mystery - inseparable from, fishing, seafaring, nurturing families and community. The painting showcases the island, which had everything the Dhivehi people needed, in itself.

Raniya Mansoor & Ali Ajikko, 2018

This work is nostalgic of how the Maldivians experienced life, as an organic whole - life, death, love, mystery - inseparable from, fishing, seafaring, nurturing families and community. The painting showcases the island, which had everything the Dhivehi people needed, in itself.

Love Local.

100% of the sales of paintings in our 2018 Exhibition go straight to our participating local artists of Maldives.

Heartfelt thanks to participating artists who donated to the Kuda Kudhinge Hiyaa Orphanage in the Maldives with their earnings.

Heartfelt thanks to participating artists who donated to the Kuda Kudhinge Hiyaa Orphanage in the Maldives with their earnings.